Chris Crawford has always been one of the most forward-looking and prescient gaming commentators, and looking back upon his writing it’s remarkable just how far ahead of the pack he was. Trip Hawkins’ EA may have claimed to have seen farther but it was Crawford who actually did. In 1981, he was anticipating the negative effects of anti-piracy solutions on consumers and, in an era of crude blobs bleeping obnoxiously, he was heralding the awesome potential of games as participatory art.

He’s developed games and written books about game development but his finest hour was the speech he made at the Computer Game Developers Conference in 1992. Even 19 years later, The Dragon speech (video: part 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) remains one of the most exhilarating and dejecting works you’ll ever read, hear or see about gaming. It is at once a glorious paean to gaming’s importance and a strong condemnation of its failure to achieve its ultimate potential. It’s Crawford at his very best with everything on display: the intelligence, the arrogance, the bluntness, the humour, the passion, the theatrics and most importantly, the insight.

Here’s what he had to say about game difficulty:

“Think in terms of a scale of difficulty with simple games at the bottom and hard games at the top. But the scale applies to people as well with inexperienced people at the bottom and very expert game players at the top. Now any given game falls somewhere on this scale but it doesn’t fall at a single point. It actually has a window. There’s the lower level of difficulty and the upper level of difficulty. When you first start playing a game, you normally start off below the lower level and what happens? You get stomped, the game clobbers you and you lose. But no problem, you come back and try it again and you learn and you get better. You start climbing the ladder and as you climb the ladder pretty soon you climb above the lower level of difficulty and you climb into the fun zone where the game is challenging and interesting and fun. You keep playing so you keep learning and you keep climbing the ladder and as you do, the day comes when you climb above the upper level. Now the game is too easy to beat. It’s boring. You don’t play it anymore. You put it aside. And then what do you do? Well, you buy another game. But this game is going to be a little more difficult than the previous one. It’s going to be higher up on the scale so you’ll climb up through that game and put it aside and buy another game and another and another. You’re just going to climb up that ladder, improving your expertise. And the result is something I call games literacy.”

(The downside of being so far ahead of the pack is when the pack does finally catch up it will have completely forgotten those who were there before, resulting in inadvertent rediscoveries of old discoveries. What Crawford described as the ladder of difficulty is now known as the Chick Parabola.)

Though that may seem like a simple observation, and one hardly worth pointing out since it would appear to be fairly obvious, it’s actually a very important one as it informs a lot of behaviours, patterns and expectations in gaming.

Games built to stand the test of time

As gamers improved their game literacy, game designs could grow in complexity, going from simple, instantly accessible arcade games designed to divest players of their coins to more thoughtful and ambitious designs that constantly gave players interesting decisions to make.

No one company better represented this gradual rise in design complexity in the 80s and 90s than MicroProse. The company started out with an arcade-inspired game and eventually went on to produce complex simulations and deep strategy games. This increase in complexity and depth happened gradually, as it indeed needed to. The hardware wasn’t ready in the early days — memory was measured in kilobytes and data chugged along at floppy disk speeds — and just as importantly neither was the general gaming audience.

Just as you wouldn’t make a child immediately go from Enid Blyton to David Foster Wallace, it would have been too much of an ask to get an average gamer in those days to immediately make the leap from arcade games to simulations. Dara O’Briain is spot on when he observes gaming is unique among the art forms in the way it imposes barriers that deny the consumer content unless they’re skilled enough to overcome the challenges presented. Gamers needed to work on those skills in gateway games like Hellcat Ace before making their way slowly up the ladder of difficulty to complex games like F-19 Stealth Fighter.

The F word

It is important to acknowledge that adding complexity to a game does not make it any more enjoyable or better. Games can be easily encumbered by extraneous detail, leaving players overwhelmed by fussy, fiddly, distracting bits that do not add anything meaningful to the experience. Complex games aren’t necessarily fun games.

Yet gaming needs complexity because some rich experiences cannot be shoehorned into simple game designs. The classic Dynamix flight simulator Red Baron taught more about air combat over the muddy battlefields of Verdun than the Atari arcade game of the same name. Indeed, no simple arcade game could hope to convey the difficulties of battling in those early fighter planes, kites so fragile they would shed their wings in a steep dive, so underpowered they’d stall during a steep climb. Short of hopping in an actual Fokker Eindecker, there was no better way than playing a flight sim to truly appreciate Max Immelmann‘s audacity and bravura as he attempted revolutionary manoeuvres.

(Source.)

Finding the right balance between complexity and fun is an art and MicroProse co-founder Sid Meier was a master of it. His games had complexity in the form of realistic details and historical flavour without sacrificing the fun factor and this was hammered home by great MicroProse designs like Pirates!, Railroad Tycoon and Civilization. He described his approach in High Score! succinctly, “When fun and realism clash, fun wins.”

This, of course, only serves to bring to mind a question Crawford raised back in 1992: why do games have to be fun? Not all books are fun, not all movies are fun, not all music is fun. Yet “it’s just not fun …” is still the most damning thing that can be said about a game. Where does the expectation games should be fun come from? Is it because most gamers first encountered games as children or adolescents and their appreciation of games remains at that stunted level?

Games are a demanding medium yet gamers don’t seem to be demanding more from their games.

By the numbers

If it’s a little puzzling why consumers remain stuck in the “games must be fun” mindset, it’s much easier to suss out the driving forces for keeping games simple and fun on the making and selling side: simple fun is easy and simple fun sells very, very well.

For the developer, churning out simple designs is easier as they likely fit existing design templates, have fewer moving parts and can be quickly produced. For the publisher, simple games are undeniably easier to market. There’s no need for in-depth explanations of how an FPS plays because gamers are accustomed to those and can simply dive right in instead of paying the fun tax of learning how to play the game.

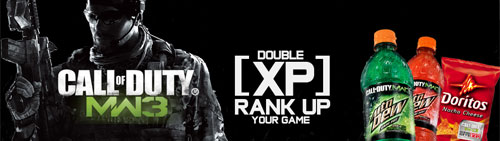

To borrow a phrase, no developer ever went broke underestimating the intelligence of the average gamer. The key to popularity and thus profits is to keep things as simple as possible: thumbstick to move, aim-assist to help target, tap this button to shoot, jab that button to switch weapons and everything else is explicitly spelt out with onscreen prompts (“Press X to accomplish the incredibly complicated task of opening this closed door”) as an embarrassing reminder of just how low the lowest common denominator is for these games.

(Source.)

Embarrassing or not, these games sell in the millions whereas complex games, aside from a few key franchises like Civilization, generally do not sell well even historically. UFO: Enemy Unknown (a.k.a. X-COM: UFO Defense), by today’s low standards a very complex game, sold 600,000 copies on the PC. If an FPS by a major publisher sold only 600,000 copies today, there would be a ritualistic disembowelling ordered at corporate headquarters.

To explain their unwillingness to support complex games like strategy games, publishers hide behind excuses like “strategy games are just not contemporary.” What they actually mean is “strategy games sell but they don’t sell enough copies to make our major shareholders’ pee-pees tingle” and the key thing to remember is the decision-makers who green light projects are shareholders themselves.

Core meltdown

If Crawford’s observation about game difficulty and game literacy perfectly captured the gaming scene two decades ago, it’s no longer applicable today. The gaming landscape has changed dramatically and in ways Crawford himself might not have anticipated back then.

There are now large swathes of the gaming population who have no inclination whatsoever to improve their game literacy. These gamers play a lot so they cannot be categorised as casual gamers but the crucial distinction is they are content to replay the same simple games with limited run-jump-shoot verb sets. They may want to play those simple games in HD, 3D and with motion or touch controls, but they are otherwise happy to experience the same familiar gameplay over and over again.

This is akin to a reader content to stick with Enid Blyton because her books are simple, comfortable and familiar. Now, those books might be fine for prepubescents but past that age, one would think that they would be ready to expand their horizons and move on to something more stimulating than the thrilling adventures of Julian, Dick, Ann, George and Timmy the Dog.

But that isn’t happening with games for a lot of gamers these days. Perhaps it’s the nostalgic longing for simple childhood pleasures, an inability to handle complex rulesets, a palate incapable of appreciating richer designs or some combination of all those factors.

Yet, just as no one should expect Justin Bieber fans to eventually move on to classical opera, there’s no reason to expect fans of simple games will improve their game literacy. There can be no accounting for taste, after all. If the average gamer (who is a 37-year-old according to current statistics) is perfectly happy playing a simple FPS or platform game, so be it.

More interestingly, Crawford’s theory also no longer applies to a lot of formerly hardcore gamers. They might have once climbed up the ladder of complexity in their younger days but these days they are climbing right back down, content to play simpler and shorter games either on the couch or on portable systems.

It’s easier to explain this. Their lives are a lot more hectic now and they have a great many other things that make great demands on their time. They can no longer spare dozens of hours learning how to play a game, poring over thick manuals dense with rules, tables and appendices. It’s entirely understandable they would use what little time they have for leisure on instantly accessible games with simple rulesets that quickly and constantly reward them for playing.

The last flight

The entirely predictable result of this focus on the simple and the easily accessible is genres that feature complex designs are a dying breed.

These games are still being developed and published in continental Europe where audiences seem to be a lot more patient and willing to give them a chance. (This has been partly attributed to the fact the European market is less inundated by games because of translation issues.) Unfortunately, the average gamer is unlikely to be even aware of their existence.

Complex games like flight simulators and deep strategy games are rarely covered by the mainstream gaming media, which obsesses over last month’s web site hits just as much as the industry it covers obsesses over sales, share prices and Metacritic numbers, because those types of games rarely figure prominently on the sales charts and are thus unlikely to get enough site hits to warrant coverage.

But the more pressing problem is the average gamer, conditioned to expect immediately accessible and instantly rewarding games, is simply not sufficiently game literate now to play complex games.

(Original image sources: 1, 2.)

The pessimist has every reason to believe this could be the last generation of gamers who remember what it’s like to play a flight sim or a wargame or a strategy game that isn’t Civilization because as things stand, the only ones capable of handling deep, complex designs are those gamers dizzyingly high up the Crawford ladder. Those gamers do not constitute a growth market and without the crucial gateway games designed to introduce new gamers to complex genres, the market for those games is only going to shrink further.

The 4 colour quandary

If there can be little doubt gaming is losing complexity, the big question is: so what? So what if gaming loses diversity? So what if gaming does get restricted to a narrow path consisting of simple fun experiences?

To appreciate the perils of going down that path, one need only look at the state of comic books in North America.

There are numerous parallels between comics and gaming, of course. Comics could boast of incredible diversity in its early decades with romance, Western, war, pirate and horror titles available right alongside the superhero titles which would eventually go on to dominate the market. Similarly, games could boast of remarkable diversity in the early years as designers experimented with the medium. There were simple fun games but these were complemented by provocative text adventures, sims of all sorts, wargames, etc. There were no niches in the early days of both mediums, just a giddy excitement as both creators and consumers explored the endless possibilities.

Just as comics had to survive scares over the seduction of the innocent when the sceptical older generation struggled to both understand the appeal of the medium and evaluate its actual impact on youth in the Fifties, games would go through the same phase of fear-mongering four decades later. It was a time when correlation rather than causality was sufficient to assign blame solely to gaming for any incident, a time when simple FPS games could be decried as murder simulators.

Just as comics went through a period of ruthless brand exploitation in the early Nineties with relaunches, spin-offs, collector-bait first issues and multiple cover variants, games are now experiencing the same thing as publishers and developers collude to produce designs calculated to extract as much money as possible from the consumer. This is the era of the sixty-dollar Smurfberry pack, and clumsy exploitation of old brands. For gaming, this is the taste of the new generation:

(Source.)

Given the similarities, it might be instructive to look at the state of comics today to get a hint of where gaming might end up in a few decades. The signs are not promising. A quarter of a century after Maus was nominated for the National Book Critics Circle Award, comics are still stuck in the cultural ghetto. That may be hard to believe since every other movie released seems to be based on a superhero comic book and comic-to-film adaptations are some of the biggest blockbusters of recent years. But comics themselves are not prospering. The top titles sell less than 200,000 copies a month now, a fraction of comics at their peak when titles that sold that amount would be cancelled. Digital comics on tablet devices don’t seem to offer any possible salvation. According to one publisher, digital comics account for less than 1% of total revenue.

The problem isn’t the medium or the delivery mechanism; it’s the perception comics are adolescent power fantasies featuring superbeings in tights beating each other up. It’s a boneheaded and ignorant perception but a very damaging one nonetheless as it results in an exasperating feedback loop that sees the top 40 titles in any given month feature superbeings in tights beating each other up precisely because the perception perpetuates the stereotype.

Is that gaming’s future? A future in which games are deemed only for those into simple, forgettable fun because those are the only games that sell well and so those are the only ones made?

The future in motion

If comics point the way to folly, gaming must look to movies to see the lofty position it could feasibly occupy in the cultural landscape.

Consider the impact of movies in the latter half of the 20th century and its continuing impact in the 21st. Movies are cultural events, newsprint and television airtime are devoted to upcoming movies and movies just released, movie actors and actresses are elected to public office, movie critics are household names, every writer has a movie script on the backburner, every movie-goer has an Oscar acceptance speech prepared. Movies are even responsible for the fame and well-being of one Michael Benjamin Bay.

It’s no surprise movies influence the way games are created and appreciated. The movie-style cutscene (the least interesting method of depicting stories in an interactive medium) is still the primary method for most games to handle narrative and game criticism still borrows heavily from film criticism.

Could games achieve the same impact as movies? Might the White House someday invite Sid Meier to solicit his viewpoints on the situation in Sudan? Will CliffyB run for Governor of California on the “Yeah! Wooo! Bring it on, sucka! This my kinda shit!” platform in the future?

That’s never going to happen if gaming sticks with the simple fun mentality. Gaming needs greater diversity — the kind of diversity movies have — if it is to escape being pigeon-holed in the cultural ghetto. Gaming may boast of titles that scratch the same itches Michael Bay does but has thus far failed to produce anything comparable to Werner Herzog and Errol Morris.

That really is the most frustrating aspect of this. Games can be so much more than what they are now.

E words

There’s one thing games can potentially do better than any other medium: empathy. This is a natural result of the control the player has over the experience. As Crawford pointed out in The Art of Computer Game Design, when it is your choice, your experience is much more personal and much more emotionally satisfying because you invest a little of yourself in every decision you make. And what is a game but a multitude of personal decisions? How better to empathise with the Other than through an interactive medium that asks so much investment of the Self?

Gaming has the potential to create experiences so moving and affecting the player is compelled into taking remedial real-world action but thus far that potential has been untapped. There are games that let the player empathise with dwarves and elves but no games that let the player understand what it must be like to be a Somalian mother scrounging for food for her starving baby. That wouldn’t be a fun experience but games should aspire to be more than just fun.

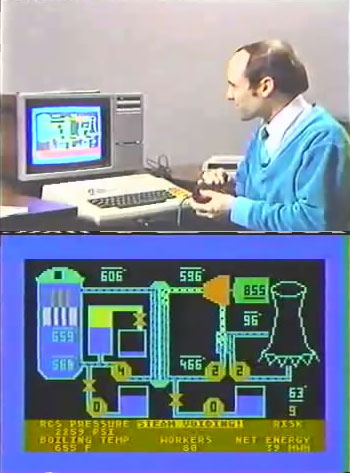

(Source.)

Gaming may be a great form of escapism but it could perhaps be more potent as a medium when it faces up to reality. As usual, Crawford was quicker to grasp this than the rest of the gaming industry. A teacher at heart, he understood early on that to play is to learn and thus gaming was a great way to explore and understand complex scenarios. In 1981, he released Scram, an Atari 400/800 game simulating the operations of a nuclear power plant, as a reaction to the Three Mile Island accident. Where is the equivalent of that today? Where is the modern game that simulates the Fukushima disaster and pays tribute to the incredible heroism of the Fukushima 50?

Fun certainly has its place in games and simple fun is absolutely necessary to bring people to the lower rungs of the Crawford ladder but there must also be games higher up the ladder that say something profound and insightful about complex situations and ideas if gaming is to have greater relevance. And gaming needs to be more relevant to people’s lives if it is to achieve greater significance in the cultural landscape.

On balance

If Chris Crawford once despaired there was no room in the industry for games that were not fun, he will soon discover for himself if that remains true. Two decades after he memorably charged off on a quixotic quest to advance interactive storytelling “for truth … for beauty … for art”, Crawford will return to gaming with a new version of Balance of the Planet, his treatise on environmental issues, and it will be enlightening to see how this Crawford story plays out.

If the gaming world at large was not receptive of the original, what will it make of the new version? It’s impossible to imagine today’s mainstream audience will embrace it but perhaps those who tire of mainstream gaming might be more receptive. After all, if Dwarf Fortress was able to find a loyal audience willing to support its making and champion it so passionately even the New York Times took notice, it can be said gamers are slowly rediscovering not all games have to be simple fun.

Superb read.

Personally I’m torn. Gaming has exploded since the early 1980s when we saw lots of experimentation although it must be said there was plenty of experimentation during the 1970s (I have just discovered a real-time strategy game called Empire was doing the rounds, prior to any development of gaming literacy, and still has a dedicated community today).

We have so many more casual gamers now. Mainstream is a bona fide big business. The public have always been devoted followers of the lowest common denominator shows because, well, they are the lowest common denominator. Everyone can enjoy The X Factor or Bay’s Transformers (I say this with some irony as I am not a fan of either) and games have followed the same grand capitalist model which has led us to pronouncements many times in TV and movies that art is dead and reality is dumber than it once was. And, as you imply, when the children of the 80s grew up they didn’t have time to burn on complex games any more, at home with the satisfying plink-smash of Angry Birds or the time-destroying grind of Tiny Tower.

All of the interesting stuff is happening in the long tail though. We have a lot of impressive indie work going on. Just to pull out one data point, Chris Park tried to do something very different with strategy with AI War. Complex simulations still exist even though there’s no large market for them. These pocket communities remain. I don’t need Activision to develop these.

But I can see your point. How does one progress from Half-Life to a nuclear power simulator? Where are the stepping stones to the hardcore end of gaming literacy? Are we actually amidst a steady decline?

Empire has been continually revised over 40 years so that it’s quite difficult for the outsider to break in. It can swamp the player in micromanagement and the interface is Linuxesque command line and I suspect the Empire community is diminishing as the years progress and not earning enough new blood to feed it. Where is the step into Empire (there are potentials, but that’s another conversation)? Does Empire deserve to survive as it has travelled so far down its own rabbit hole that it can’t make it back out?

I am pessimistic with a streak of optimism. A period of loss is followed by a period of renewal: it is cyclical. Every time we think we’ve lost everything good and great, there’s a resurgence of innovation and art. I’m British – and we used to joke about American TV being useless for high-brow television drama but now it throws out The Wire, Deadwood, Mad Men and a host of other excellent dramas. We were already lamenting the consolisation of gaming ten years ago, that the good old days of complexity were gone – but now indie gaming is fiercely strong. There are efforts to make games that teach things and explore ideas that do not involve guns or dragons. It’s when we all agree we miss something – then something gets done to fill that gap.

The real fear I have is funding. I don’t see money moving around this gaming ecosystem as freely as I’d like. It gravitates towards popular games who are forcing the prices down wholesale (that’s a gross simplification but I can live with it for a moment). Even niche games are being mocked for having “ridiculously high” prices. Without the money to fund development, and complex games to some extent are just as expensive to make as a high-powered uncanny valley FPS, the complex end of the spectrum will starve, wither and die.

(There are also larger issues about consumer culture and living in an instant gratification machine, but Jesus I think I’ve written enough already.)

I appreciate the trouble you took to not only read the post but compose a thoughtful and lengthy comment. I think I said what I needed to in the post itself but I’d like to touch on some of the points you made.

You point to Empire as an example of a game that existed prior to the development of game literacy but there are a couple of interesting wrinkles there. If it’s the same Empire I’m thinking about, it’s turn-based rather than real-time strategy and that game was almost certainly geared towards gamers who developed their game literacy through even more complex board games, miniatures games and wargames from publishers like Avalon Hill. And playing as they did on mainframe computers at universities in the 70s, those gamers were by no means the average gamer I was referring to in the post.

(Interestingly enough, one of the people who worked on the commercial version of Empire, Mark Baldwin, went on to create The Perfect General, which was essentially a beginner’s strategy game. It was an ideal first rung on the strategy ladder in 90s, which could naturally lead to Panzer General’s beer-‘n’-pretzels approach in ’94 then later to Gary Grigsby’s Steel Panthers in ’95 or the more grognard-y Talonsoft games, and perhaps even back to the contemporaneous version of Empire.)

I’m less optimistic about the indie gaming scene since I don’t believe they have as much freedom as most believe they do. As Brian Moriarty pointed out in his An Apology for Roger Ebert speech, most indie game developers have no cushion for failure — Chris Park’s Arcen Games, for instance, was flirting with bankruptcy in November 2010 when Tidalis didn’t fare as well as hoped — and whatever creative decisions they make will be tempered by that knowledge.

Ultimately, gamers will get the games they deserve. If they remain insistent games should remain within that narrow spectrum going from childlike wonder to adolescent fantasies, that’s precisely what will happen since there’s no impetus for change and evolution.

I just think it’s a shame that a medium with such great potential should hamstring itself so early in its history.

Ah now Empire is tricky! The Empire you’re thinking of is the turn-based one that was created by Walter Bright. The one I’m referring to is Peter Langford’s 1972 Mainframe creation which is (scheduled) turn-based inputs with real-time events; it’s very much Neptune’s Pride but a lot more complex, especially in its modern incarnation. I’ve been writing about Empire this week so it’s at the forefront of my mind =) I don’t know if we have a bridge to the hyper-complex modern version of Empire; although one of the ex-Empire developers has recently produced something called Strategic Initiative which on the surface seems to be a much simpler version of Empire.

I think pretty much we agree on the indie side of things. My fear about funding is the same as yours. I find it dispiriting that prices of all games except mainstream have now slid into the bargain basement zone and you’re only going to make serious money off that if you sell well – which as you point out is going to hobble the development of anything in the area of complexity. Markup niche pricing can work, of course, when you look at Cryptic Comet’s output.

But, still, I see more trouble here than anything approaching security for most developers.

I swear I left some comments here…

Agh. My proxy hid them! Sorry for the rubbish comments asking where my comments are. Anyway, I am going kick this over to the Rock Paper Shotgun Sunday Papers and see if they like it.

Came here from RPS Sunday Papers.

A great read.

Yes, i also came from the Sunday Papers, the lovely RPS Weekend Edition.

To quote Kynrael, its a great read-no, its fucking fantastic. You´ve summed up quite nicely what i´ve been thinking for some time now. I´d consider myself very high up the ladder-just recently started “playing” X-Plane (altough a lot of Simulation Types seem to be very specific about it not being a game…) I love complexity in games. I also love micromanagement (kind of)-as long as the things you do are still meaningful decisions. I always wanted to get into Dwarf Fortress but the UI, or lack thereof always kept me from playing it. I have to be honest here: It seems to be such a lovely game but thats too much, even for me. Presentation IS important and shouldn´t be overlooked. Take the Anno series, or the new Patrician… yes, they are german, but very attractive looking and have a modern interface. I really forced myself to like DF but couldn´t. Sometimes i feel like people are so proud of being so hardcore and niche with nobody getting what they do that they feel this kind of barrier is needed. Of course that´s exaggeration, but complexity sure is possible if you open up the interfaces and the graphical quality. Just think about how many people would play Call of Battlefield if you´d have to navigate fifty menus filled with lots of text to shoot your gun.

Addendum: As a reference for doing it right, just look at the new Civ5. It´s a very complex game where you can really micromanage a lot of things but you don´t have to. I disagree with people saying that keeping all of the mechanics under the hood is making the games bad. But i am not a fan of dumbing things down either. Referring back to my mention of Flightsims: They are very complex and involve huge amounts of micromanagement but almost all of those options are vital and meaningful (flaps for take-off, gears, navigation) and add to the immersiveness.

I find this somewhat interesting, but for the most part I disagree with the idea that depth in games relates directly to their mechanical complexity.

Evaluating art in terms of how difficult to understand it is doesn’t make much sense to me. I’ve read books and watched films with extremely complicated plots and for the most part that doesn’t make them better works of art. Same goes for games. It bugs me that Crawford seems to equate complex games with a more ‘elevated’ experience, which suggests a vision of games simply as a series of challenges, but then compares them to books and music, both mediums where more complex doesn’t equal better at all.

If you think games should be about making the player feel something, then why should you constrict yourself by having to challenge them?

I’m not so sure what the problem really is here. You can troll plenty of niche wargame forums to find niche wargames if you’re looking for them, but you do have to pay, and be willing to put up with stuff that’s rough around the edges.

Also, i’m not terribly sure you can’t make an un-fun game if you want to, but you really can’t expect to make money doing it. If I make a Quartermaster game where you work as a book-keeper for a US Army division in world war II just to make some kind of point on the banality of war, I can’t reasonably expect people to shell out 50 bucks for it.

Everything goes through cycles. I enjoy some modern games, but many modern games are tasteless and poorly designed. All modern FPS games can’t hold a candle to FPS games made almost a decade ago in terms of mechanics, Unreal tournament 2004 and Quake 3 being pretty much the pinnacles of the genre. So even in a mainstream genre like FPS we’ve had regression with halos regenerating shields and two weapon limits.

The dumbing down started around 2000’ish PC 3D hardware caused huge market fragmentation in the PC space and consoles were cheaper. Many PC devs had no business sense back then and chased technology till they went out of business (interplay) and the developers went over to console land or in hardship they got acquired.

The rapid pace of technology actually is what is responsible for gaming having to quickly find new revenue sources to support the extreme increase in development costs and team sizes. Even console developers were not immune to these pressures. Almost all games from the ‘hd era’ from PS2 onwards have significant issues not losing the flow of the games fun. So there’s been a reduction in game quality across the board in many AAA titles as the game industry had huge teething problems scaling up. Major game corporations are still suffering from this even to this day.

A case in point are open world games – they cater to lowest common denominator, things like Oblivion and skyrim are games that cater to low brow tastes. They could be good games but the pacing in an open world is hard to manage and the actual games are missing, there is too much simulation of the mundane. A game like Grand theft auto works because there is a lot to do within its world, other “open world” games that are not GTA are pretty horrid because they lack variety and pacing.

As graphical realism increased many mundane aspects of the real world came to the forefront also. I can’t stand games that are poorly paced and don’t ‘edit’ out the bad boring parts that should not be there.

As for “complex games” having died out, some complex games died out but other genres actually increased. Racing games are one of the few genres that actually increased in complexity even the ‘casual’ ones like burnout 3 and their sequels. Complexity hasn’t been lost it’s a matter of the audience being able to handle it and in what way and whether the size of the audience is there to justify making said game.

What the game industry has slowly learned is that theme and presentation matters, we are in a ‘post gameplay’ era. At least with the casual audience of AAA games, since fidelity is at a point where you can use cinema/story to sell the game even if your gameplay sucks, mass effect 1 is a case in point – huge sections of the game are poorly paced and there is scarcely anything to do on the planets. It sold primarily on story/characters/compelling universe.

The reason older story based games like planescape torment bombed was it was made at the wrong time with the wrong budget and presentation.

If you wrapped torments story in AAA cinematic trappings of todays games (mass effect 1/2) and theme swapped for forgotten realms tolkienesque art design you’d have hit on your hands.

The casual audience has narrow aesthetic tastes that demand AAA budgets that either go for realism or a motif that is accessible by a large section of the public.

As for some of the commenters that don’t get what you’re saying. I’ll talk of my own experience. I’m an all around gamer, PC, console, wherever. I grew up NES in the 80’s and then got also got into pc gaming in the 90’s.

Even console games are suffering from what the author is talking about – take Nintendo’s zelda, the combat in zelda games has not learned anything from other action games that have done it better over the last 10 years. New entries in the series are just stale to someone who grew up on zelda during the late 80’s and early 90’s.

The last good Zelda was Ocarina of time, ever since then nintendo has just been repeating the same game over and over, with the japenese not learning lessons from other action games by both japanese and american game companies. The gameplay systems in Zelda haven’t evolved in interesting directions and the few times there is an interesting evolution, like wind-wakers slightly more involved combat with certain enemies where there is a variety of ways to interact with the enemy, it’s few and far between.

Many game developers don’t even understand the essence of what their games are to players – Zelda is primarily an action oriented dungeon crawler which does action poorly and tries to throw in a crappy story.

We can take another series from the console world – starfox. Starfox franchise was one of my favorite but it was ran into the ground by Nintendo during the gamecube era in an effort to make it appeal to a casual audience. Both adventures and assault completely upended the genre of the game from flying-arwing space shooter to poorly realized 3D action/adventure game and notice the horrible metacritic rating of Starfox assault, the last starfox game for a major home console. A total abortion.

There was a major falling out between the developer of starfox and the legendary Miyamoto (who is a complete idiot for screwing up one of nintendo’s best franchises). Many developers have become completely stagnant and are afraid to make ‘more hardcore games’ even in casual friendly console land.

thecreepyhour, that’s not the argument being made by Crawford at all and I’m not sure where you’re getting “Evaluating art in terms of how difficult to understand it is …” and “Crawford seems to equate complex games with a more ‘elevated’ experience …” from. As I noted above, adding complexity to a game does not automatically make it any more enjoyable or better. Let it also be clear Crawford is actually in favour of simplicity in games. It is my contention that some experiences cannot be shoehorned into simplistic game designs.

That Atari Red Baron arcade game was picked as an example for two reasons. For one thing, it inspired MicroProse’s founding. But there’s also a Crawford connection. The game was cited in Crawford’s 1982 book, The Art of Computer Game Design, to highlight the difference between games and simulations. Crawford notes, “RED BARON is not a game about realistic flying; it is a game about flying and shooting and avoiding being shot. The inclusion of technical details of flying would distract most players from the other aspects of the game. The designers of RED BARON quite correctly stripped out technical details of flight to focus the player’s attention on the combat aspects of the game. The absence of these technical details from RED BARON is not a liability but an asset, for it provides focus to the game.”

That was written in 1982 and eight years later, the Dynamix flight sim showed Crawford was wrong about this. You could add technical details, more realism, more historical flavour and, far from cluttering the design and being detrimental to enjoyment, this complexity, when incorporated shrewdly, could enrich the experience and even make for a better game. In 1996, Dynamix’s Red Baron placed an impressive fourth in Computer Gaming World’s list of top 150 PC games of all time even though the magazine pointed out “(w)ith all the realistic options turned on, Red Baron is a bear to fly …”.

The Red Baron arcade game was designed to let anyone insert coins and immediately have a blast; the Red Baron flight sim required far greater game literacy but the payoff was both visceral thrills and actual insight. If you simplified the flight sim (say, in order to increase marketability), it would lose its significance.

The greater argument being made is when the industry is conditioning its audience to expect instantly accessible and immediately gratifying gaming experiences, the medium is going to lose out in the long run when that audience immediately rejects any games that aren’t simple and aren’t fun.

If you’re looking for a “tl;dr”, Alan Kay (the computer scientist mentioned in The Dragon speech) put it best, “Simple things should be simple. Complex things should be possible.”

Panzeh, the problem you’re overlooking is gamers hungering for those niche gaming experiences — fun or otherwise — might not have the game literacy necessary to play them.

Ricemanu, I’m not discounting the possibility there are hardcore gamers who take immense pride in the inscrutability of their complex games but as a Dwarf Fortress fan, I’m always a little disheartened whenever I hear curious gamers are too intimidated to play one of the most extraordinary games of all time. As I noted in a recent MetaFilter thread, Dwarf Fortress is highly unusual in that it’s meant to be a life’s work in an industry that routinely orphans its products. It’s only one-thirds done at this point and I suspect the Brothers Adams are too busy working on the feature-set to improve the UI but even at this stage, Dwarf Fortress has already provided me with indelible gaming memories and I can point to even greater stories shared by other passionate fans. If you’re really keen on trying it out, the good news is Peter Tyson (a.k.a TinyPirate/Calistas) will publish a Dwarf Fortress tutorial for O’Reilly Media titled Getting Started with Dwarf Fortress (subtitled “Learn to play the most complex video game ever made”) in April. I hope this gets more players into the game and sharing their own incredible experiences.

BOBC, thank you for taking the time to share your thoughts.